loading...

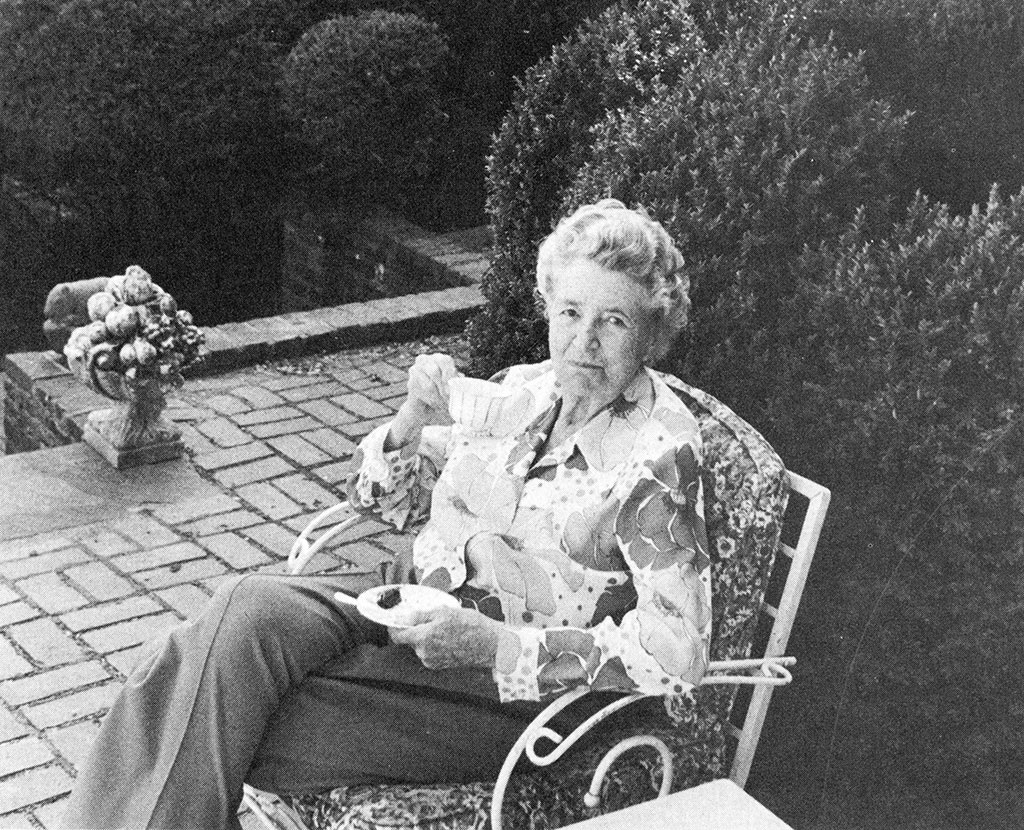

American Craft Council and Aileen Osborn Webb

by Emily Zaiden

It is the things of the spirit, the arts of the country, which have always led mankind forward, and it is to this spirit that the craftsmen of the world must lend themselves.

-Aileen Osborn Webb, 1964

No other organization has played a more important role nationally in the history of American crafts than the American Craft Council. Without the dedication and persistence of leading art patron and philanthropist Aileen Osborn Webb, the group might never have been created.

Origins

Webb was born in Garrison, New York in 1892 to William Church Osborn and Alice Dodge. William came from a family that had investments in mining, railroads and real estate and he became a prominent supporter of medicine, culture and the arts. William’s father had been an early force in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and William became the president of the board of trustees from 1941 to 1948, bequeathing the museum most of his private collection. Art patronage was in Aileen’s genes.

Her mother’s side of the family had amassed their own fortune through mid-19th century metal importing and industry and become American royalty. The Dodge family was well known for their charitable generosity. Her mother’s sister Grace was a social reformer devoted to aiding working class women. May Cossitt Dodge, Alice’s cousin, inherited a large copper fortune that eventually landed in Aileen’s hands, allowing her to broaden her support for art in all mediums.

Aileen married Vanderbilt Webb, the youngest son of Dr. William Seward and Lila Webb, in September of 1912. “Van,” as she called him, was a lawyer and heir to the Vanderbilt shipping and railroad fortune. His affluent family was deeply immersed in the world of philanthropy. After creating Vermont’s railroad, the Webb family had established an enclave in the late nineteenth century in Shelburne, on the banks of Lake Champlain with sweeping views of the Adirondack Mountains. Aileen and Vanderbilt eventually inherited the family farm on the property but their main residence was a home on Park Avenue in Manhattan and they also had a cottage in Aileen’s hometown of Garrison, New York.

Aileen Osborn Webb was actively involved in politics from an early age, shaped by her family’s Democratic orientation. She felt a responsibility to realize her ideals to positively shape American society. She was equally interested in art and she recognized the way that art could also influence and inspire people so she studied art and then focused on promoting the handmade. Coming from a family of entrenched fine-art supporters, Webb was able to use her influence over the years to convince other powerful art patrons that craft had inherent artistic merit and depth and that it was an important part of America’s national heritage. She fought to earn a position for craft within the art world.

Strategies for Spreading Craft: Marketing

In 1929, she formed a marketing group with friends in Garrison for “selling whatever a person living in Putnam County could make or produce.” The timing was noteworthy as the U.S. was on the brink of economic meltdown and Webb saw the need to aide struggling Americans. Webb admired the self-sufficient nature of craft production as well as the inherent artistic spirit that was instilled in the wares. This initial effort was the origin for Putnam County Products, a shop that they opened and expanded in that part of New York state in 1936 and 1937.

Putnam became a home-industry program through which Webb and her colleagues marketed agricultural products, quilts, pottery, and other handmade, traditional wares produced in rural areas to urban centers in the northeast. Webb’s goals were perfectly aligned with the New Deal era and the WPA projects that provided opportunities and assistance for artists. Throughout her life, Webb stated that she felt it was a privilege that she was able to help those less fortunate. “Money…has never meant much to me except that it gave me the freedom to say “yes” to people who asked for help.”

In August of 1939, Webb hosted a small group of representatives from various craft regional leagues and guilds at her summer home in Vermont. The result was the formation of the Handcraft Cooperative League of America. In forming the League, Webb managed to unite the smaller craft groups and begin the drive for a national craft movement. In 1940, they incorporated in New York and focused on their goal of opening the distribution channels for rural crafts in metropolitan centers.

Webb and her fellow advocates believed that if people could have a better understanding of handmade objects and more access to them, crafts would thrive and have an influence on mass-produced design. She was also driven by the simple notion of bringing beauty into people’s homes and lives through crafts. As a result, the league established America House in 1940 as a cooperative shop at 7 East 54th Street in New York, where American-made crafts could be purchased.

Operating during World War II, America House was partially motivated by the patriotic idea of supporting through purchase goods and objects that were made by Americans, using traditional methods, local materials and historic techniques. Webb avidly believed in the moralizing power of handwork. Webb and her partners felt that the more crafts that sold, the more peoples’ lives would improve, not only on an economic level for the artists, but a deeper level of meaning for the purchasers, as well. In addition, now, a brand new channel for purchasing crafts existed, and better yet, it was a prime Manhattan location.

America House took root during the war years but truly flourished in the post-war boom era. Postwar prosperity, increasing mechanization and the rise of consumer culture in the 1950s energized the craft community.

America House went through three relocations and operated for thirty years. The craft outpost finally closed at 44 West 53 Street in 1971, but only after it’s success had created a market for craft and inspired hundreds of craft outposts, galleries and shops to open across the country. Handmade art objects were in high demand. Thus, Webb achieved her vision of expanding the American craft market and making it highly accessible and desirable to the American consumer.

Strategies for Craft: Organizing the Community

In addition to the League, another leading group that was active at the time, the American Handicraft Council, was incorporated in Delaware and founded by Anne Morgan, daughter of John Pierpont Morgan, who was Webb’s NYC neighbor and friend. The two organizations had related goals: Webb’s league, with the participation of a broad coalition of craftsmen, was dedicated to promoting and distributing rural crafts to urbanites whereas Morgan’s council concentrated more on teaching and craft study.

In the first years after their founding, the groups worked separately to enhance the status of crafts in America. Then, in May of 1942, realizing that they would be stronger if they merged, they became the American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council, Inc., which flourished under Webb’s leadership for many decades.

In 1943, America House moved into a building at a prestigious location on Madison Avenue. It was in this space that the Council was able to expand its activities. Webb hoped that they could hold more workshops that would raise awareness and also train new craftsmen. As the council expanded its education efforts, Dartmouth began creating a manual arts training program for rehabilitating war veterans, which the council eventually sponsored.

Strategies for Craft: Education

To effectively “provide education in handcrafts and to further stimulate public interest in and appreciation of the work of handcraftsmen,” the American Craftsmen’s Educational Council was created in 1943. It was Webb’s wish that aspiring craftsmen could receive legitimate academic training and learn essential skills at the top American universities. She hoped that by expanding educational opportunities, people would learn to create higher-quality objects. This new branch of the original American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council sponsored public programs, seminars and competitions.

In 1943, the American Red Cross had initiated a program to teach returning veterans pottery, metalwork, bookbinding, woodcarving and other crafts through the help of volunteer instructors. Webb had met a soldier who persuaded her to consider creating a school based on this model. The encounter gave her an extra push and validation of the therapeutic and redemptive powers of handwork.

Webb initiated the School for American Craftsmen at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, which opened in 1944. It symbolized that craft training was not merely a technical vocation, but rather, it was placed alongside the fine arts, design, and engineering in the realm of academia.The school briefly shifted to Alfred University in the summer of 1946. Since 1949, the school has been part of the Rochester Institute of Technology where it has flourished.Today, the school is a part of the multi-disciplinary College of Imaging Arts and Sciences, where film, art, design and print media all come together to cross-fertilize one another under one branch. The goal of the school has been to elevate and advance the standards of American hand work. It helped spawn programs at other American universities.

Strategies for Craft Advocacy: The Printed Word

In keeping with its mission to publicize and increase visibility for the crafts, the Council started printing an early newsletter for members that became the vehicle for reaching a general audience who wanted to stay informed about the craft world. The newsletter quickly developed into an actual magazine. The first true issue of Craft Horizons was published in May 1942 with 3,500 copies.

Many of those who received awards from the competition went on to become the best in their fields, including jewelry maker Betty Cooke, ceramic artists Wayne Higby and Robert Sperry, and many others. The competition exhibitions expanded the audience for crafts and multiplied opportunities for artists. They provided an environment for bringing fresh forms of expression and cutting-edge concepts to the forefront. The last show was in 1988, at which time, largely due to the success of Webb and her organization’s efforts, craft had become its own force within the mainstream art world.

In light of the success of the competitions, and recognizing that education needed to be the focus of the overall mission of the council, the American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council was dissolved into the American Craftsmen’s Educational Council in 1951. Weaver Dorothy Liebes and painter-ceramist Henry Varnum Poor became some of the first craft artists to serve as trustees.

Soon thereafter, the reorganized Educational Council put on the juried exhibition, “Designer Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953,” bringing together the work of top craftspeople from across the United States into one comprehensive forum for one of the first times in American history. 243 works by 203 craftsmen were selected.

With the show, the Council wanted to appraise the state of American handmade work and showcase the brightest and finest. The exhibition made it clear that contemporary crafts were sophisticated, evolved, and complex. The exhibition was also aimed at inspiring craftsmen to consider aesthetics, design, and technical excellence. The exhibition was supported by the Brooklyn Museum, where it premiered, and it traveled nationally to the Art Institute of Chicago and a total of ten major museums. The Council sponsored the show again in 1960 and it featured the work of artists from across the country.

The council was constantly evolving during these years and emerging as the leading authority and shepherd for craft within the art world. In 1955, it abbreviated its name to the American Craftsmen’s Council, which reflected its broadened image and purpose.

Webb had always tried to create opportunities for artists to come together and meet like-minded artists and to unify the craft community through meetings and gatherings. One of the more significant events was the council-organized first national American craftsmen’s conference, which was held in Asilomar, California, in 1957. 450 people attended and a series of conferences then followed this one.

Webb hoped that by creating a forum for artists to convene, they would be able to trade methods, sources, materials, practices and experiences and to cross-fertilize each other’s work. From 1960 into the late 1970s, numerous regional conferences, programs and workshops were held that followed the Council’s model and many independent regional groups and organizations expanded and emerged.

The council was invited to select 130 craft objects included in the U.S. Pavilion of the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. The opportunity was a tremendous push to place American craft in the global spotlight. Webb was aware that American crafts needed to be promoted beyond the states for them to become fully validated.

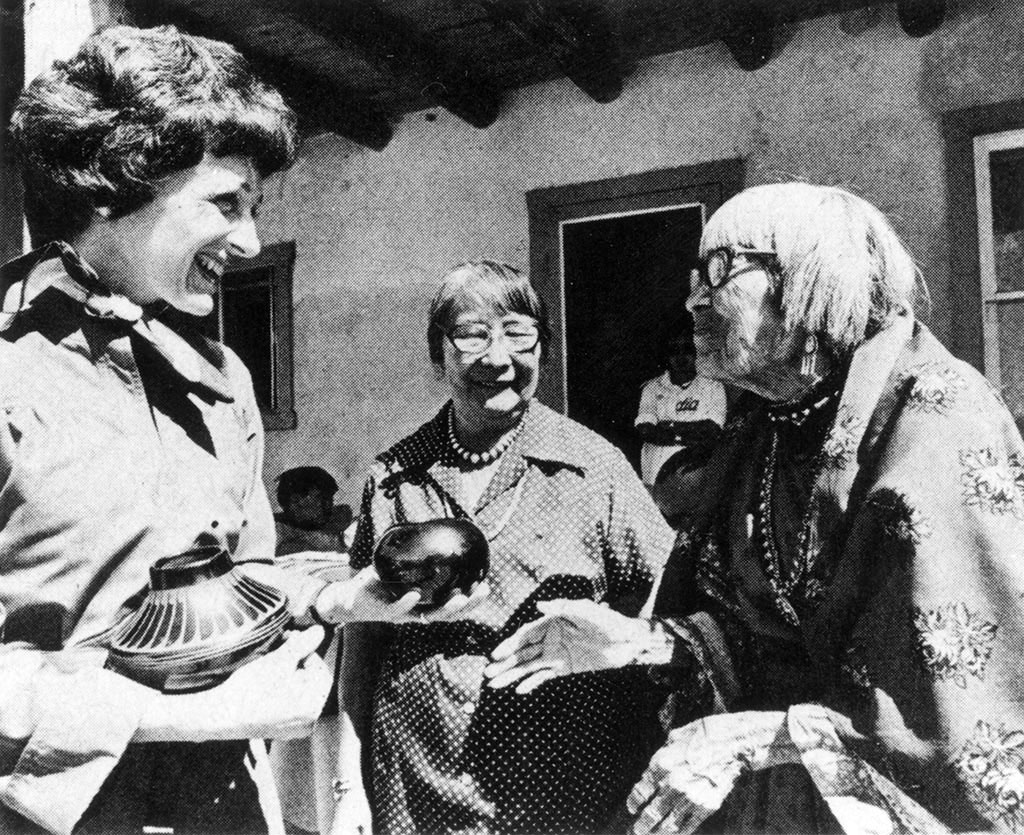

In 1964, at the time of the World’s Fair, Webb and the council got more ambitious and invited craftsmen from all over the globe to participate in an international conference at Columbia University. The First World Congress of Craftsmen brought together artists, collectors, scholars, and curators. Their goal was to form the World Crafts Council. Webb began thinking about the concept with Margaret Patch in 1962. Webb hoped that by opening up the channels of communication and creating an opportunity for the group to convene, enriched cultural understanding and exchange would be possible. On a leadership front, councils in other countries, including Canada, Australia and the UK were formed that were patterned after the American Crafts Council.

Establishing a Museum for Craft

Webb and the council’s most important contribution, by far, was the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, which opened on September 20, 1956, in a renovated Victorian brownstone at 29 West 53rd Street in New York. The building was beside the Museum of Modern Art, thus placing it symbolically on par with the prestigious art institution.

As a result of its previous work and achievements, Webb and the Council recognized the need to find a permanent site where the public could see craft objects in the flesh in an official gallery setting. Through the new showplace and office base, the council hoped to raise awareness about the highly-advanced level work of American craftsmen and to show how contemporary handmade crafts could enhance modern life in an age of machine-made goods.The opening of the museum in the heart of New York City, right near the established major art institutions, was a monumental achievement for the status and legitimacy of crafts in American culture.

David Campbell, a Harvard-trained architect who later became museum director from and also president of the American Crafts Council, renovated the building that housed the museum. Campbell had worked with Webb dating back to the formation of the Handcraft Cooperative League of America in 1940. He had also been integral in forming the craftsman program in New Hampshire and in promoting crafts through regional programs across the states.

According to Webb, Campbell was “obsessed with the conviction that the creative use of the hands was one of the things which the world needed.”Webb and Campbell formed a powerful partnership based on mutual respect. Their individual strengths came together as a collaborative team, motivated by shared utopian idealism. Campbell split his time between the Council, an architecture practice, and directorship of the New Hampshire League of Arts and Crafts. He also designed Webb’s penthouse on East 72nd Street, where he stayed part of the week.

Campbell and Webb wanted to link the Council with respected professionals and art patrons in order to ensure that craft be honored for its sophistication and vitality.They hoped to bring attention to the innovative, fresh, accomplished work of the hand and they were driven by the notion that it deserved a spotlight.

Campbell furthered Webb’s vision by transforming the building into the world’s first exhibition space devoted to craft. The building had lower level galleries and airy upper floor Council offices. Campbell’s modern design fulfilled Webb’s wishes. Webb stated in various interviews that she was exhilarated by the year-long process of opening the museum.

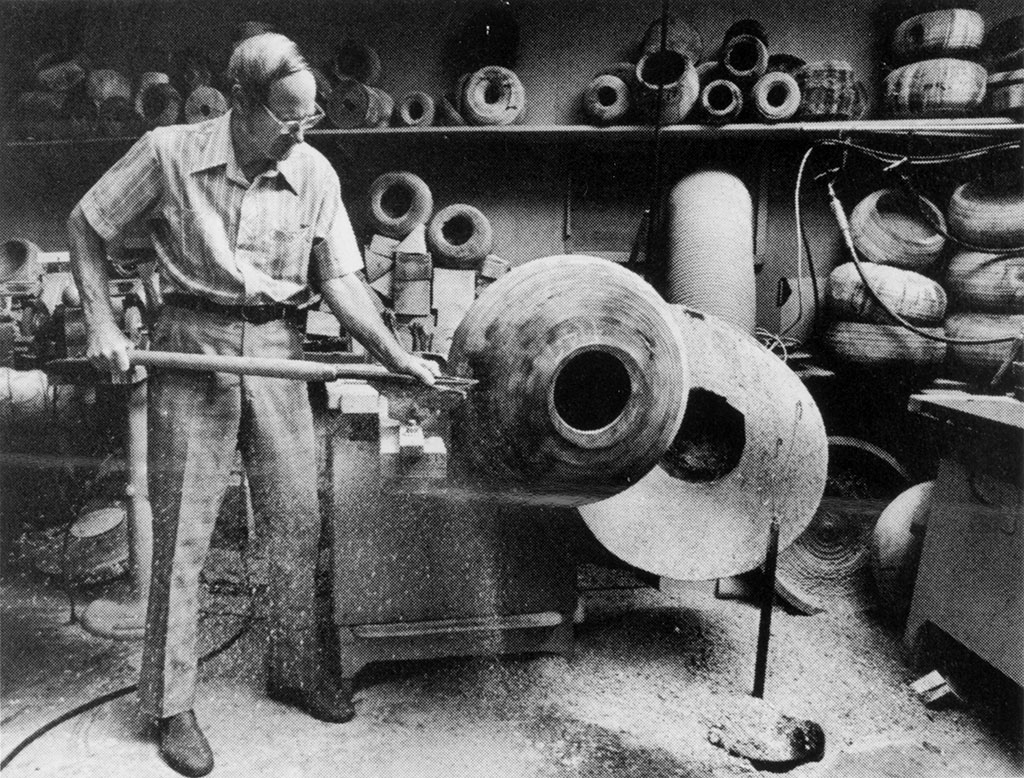

The museum made its debut with a show called “Craftsmanship in a Changing World,” which explored the role of craftspeople and their influence on design. The objects that were included displayed a mastery of technique and an appreciation of various traditional craft materials, such as ceramics, fiber, glass, metal, and wood. The museum began assembling its own permanent collection around this time under the direction of Thomas Tibbs, who helped launch the new space. It also held its first single-artist, living-craftsperson show on woodworking master Wharton Esherick that year, ushering in a wave of individual artist shows over the years. Tibbs held the directorship until 1960 when he was followed by David Campbell.

When Campbell died in 1963, Paul J. Smith became director. Smith, who was a jeweler and woodworker himself, had joined the staff in 1957, working as Campbell’s assistant. During his tenure, he brought to the museum some of the most progressive craft exhibitions ever held. They held a mix of artist-based, thematic and design-oriented shows during that era.

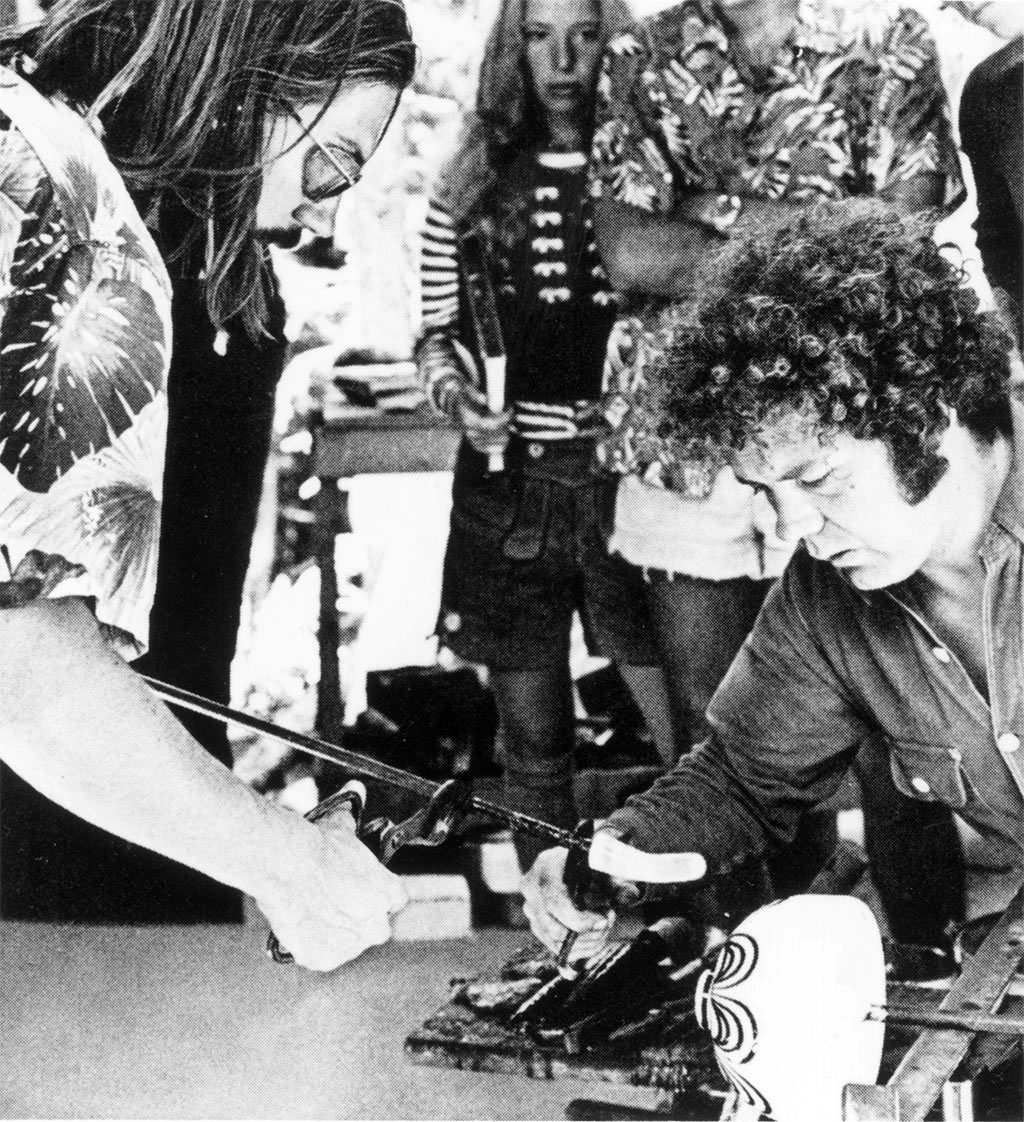

In his first year, the “Woven Forms” exhibition explored the potential of fiber, reflecting the new direction it took as a medium during that decade. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Smith guided the museum to focus on innovations and vibrant currents; shows became participatory, and objects were less functional and more communicative. The museum explored the design connections between craft and industry during this era. The museum became a voice for articulating the dynamic craft activity that was taking place across the country.

With so much success in New York and with such an active craft community in the West, in 1963 the Council opened a West Coast office and exhibition space that was provided by the Oakland Museum. Soon, it was offered the opportunity to open a second museum on the West Coast. Ghiradelli Square had just been developed and opened to the public and Webb was offered space for a museum at the location. The Museum West at San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square debuted in 1965, with a show called “17 Craftsmen of the West,” however it only remained open for three years because it became very expensive to operate and never received full supported from the local community.

The 1960s and 1970s were a time when craft became a fertile branch within the arts. Craft schools, centers and programs were thriving largely due to the Council’s successes. Craft finally entered into the national conscience as a vital part of the art world and an important expression of national identity. Then, in 1976, Webb resigned as chair of the Council and Barbara Rockefeller came in to succeed her. Webb died on August 15th, 1979, and the following period brought several significant changes.

To begin, the American Crafts Council was renamed the American Craft Council, and the Museum of Contemporary Crafts became the American Craft Museum to unify the branding of the organization. After selling the property at 29 West 53rd Street to the Museum of Modern Art in August of 1978, the American Craft Museum reopened at 44 West 53rd Street with a furniture show the following spring in a building that Webb had purchased in the late 1950s. America House had moved there in 1959 and it had been shared with the Council on two floors.

In 1982, American Craft Museum II opened with a show about the history of American papermaking at International Paper Plaza on 45th Street. Museum II doubled the gallery space and remained open for three years.

In 1986, the museum opened in an expanded facility at 40 West 53rd Street. Developers CBS and Gerald Hines Interests agreed to provide the new space in exchange for the land and structure at 44 West 53rd. They replaced the previous building with a new tower by architects Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo. The museum moved into an 18,000 square-foot, three-level, ground-floor facility in the tower with interiors by Fox and Fowle Architects. It doubled the museum’s size.

Re-incarnation: The American Craft Museum Opens

The inaugural exhibition in the new space was entitled, “Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical.” This major survey explored the role of the handmade in an increasingly technological era, and the important link between hand and spirit. With its catalog, the show helped bring crafts to the public eye and it toured for two years. More than 300 pieces were included made by 286 artists. Some artists were well established and internationally known and others were just emerging. Some of the objects were functional while others were purely conceptual.

Through the 1980s, the American Craft Council’s work and its museum shows were the most vital of all craft institutions, a model for other arts organizations. The council also made enormous efforts to spread craft abroad, while it had successfully inspired regional craft organizations and groups to emerge across the states. After directing the museum for twenty-four years of its expansion and development, Paul J. Smith retired and became director emeritus in 1987. Smith curated an ACM-organized 1989 show, “Craft Today USA,” an adaptation of the previous show by the same name. The new, 200-object show opened at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris and it traveled to 15 cities over the next two years.

In 1990, the council and the museum recognized that they needed to become two separate entities, so they split. The Council moved to a space in SoHo, where they expanded the library. The museum began a decade-long project to chart the history and diversity of crafts in America in the 20th century with a program that included symposia, exhibitions, and publications. Under director Janet Kardon, the project came together with the help of more than 100 craft scholars and artists. The three shows and accompanying catalogues chronologically examined the craft movement from the turn of the century to the mid 1940s. They explored the social, political, and economic role of the crafts and the cultural impact of the shift from industry to technology.

In 2002, the museum changed its name to the Museum of Arts and Design, reflecting the new position of craft and its integration with the other disciplines. In September of 2008, the museum moved to a renovated existing building designed by architect Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture at 2 Columbus Circle in New York City, near the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and the southwest corner of Central Park. The new facility tripled the collection, exhibition, and programmatic space for the constantly growing institution to a total of 54,000 square feet.

Today, the museum serves an educational purpose, offering more than 75 public programs a year, including presentations and workshops for children and adults. With a world-class collection of more than 2,000 objects, mainly made by American artists, it provides a home for the crafts, bringing them prominence and validation. The museum has several support groups that give members the chance to visit artist studios and meet other collectors, scholars, and artists, creating an unparalleled community.

Meanwhile, the Council remains the primary national voice for unifying the American craft community and organizing major craft fairs and juried shows across the United States. In addition, it maintains a specialized library and archival collection. It recently relocated to Minneapolis. Each year the council presents the Aileen Osborn Webb Awards to honor individuals and organizations that help advance the crafts, and it continues to develop educational strategies that elevate and expand people’s ideas about the notion of craft, bringing groups together, sponsoring seminars, and offering grants.

Webb’s legacy lives on in the museum and the council, American Craft magazine, the craft collections at most major museums, and the hundreds of craft organizations, schools, centers and galleries that now exist across the country.

__________________________

Images courtesy of American Craft Council.

Kardon, Janet Ed. Craft in the Machine Age: The History of Twentieth-Century American Craft 1920-1945. New York: American Craft Museum, 1995.

Smithsonian Institution Research Collection- American Handicraft Council records, www.siris.si.edu

Webb, Aileen Osborn, Memoirs 1977, Diaries in the Archives of American Art.

Busch, Akiko. American Craft Museum: Forty Years 1956-1996. NYC: American Craft Museum, 1996.

American Craft Council website, www.craftcouncil.org

Craftsmen USA 66, pamphlet.

Smith, Paul J. Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical. NY: American Craft Museum, 1986.