Bernard Kester

Bernard Kester; Conduit for California’s New Crafts Movement

By Emily Zaiden

Artistic movements are driven not only by artists, but by those easily overlooked figures from behind the scenes who help bring the work to the forefront; the curators, the art teachers, and the writers. Bernard Kester has worn all of those hats with exceptional ease, and imaginably little sleep, over the course of his career. He was as prolific in his undertakings as he was versatile. His curatorial work, paired with his role as an art professor, allowed fiber to become a medium for contemporary art. In addition, he was an active participant in the burgeoning studio craft scene in California during the 1950s and 1960s, generating work that encapsulates the best of the mid 20th century design ethos. His indispensable contribution helped usher in an entirely new era for craft in the twentieth century.

Kester is fiercely opinionated and yet simultaneously elusive. In his writing, he was precise and decisive. He strives for and achieves nothing short of visual harmony, subtlety, and perfection in his design work. I had the pleasure of asking this serene and timelessly elegant man about his past. When he arrived for lunch sans-bowtie, I took it as a sign that he was willing to open up and reveal a bit about himself.

Kester was born on March 25, 1928 in Salt Lake City. His parents were making a pilgrimage from Colorado Springs, Colorado to sunny Southern California. The couple had met and married in Colorado Springs, his father’s hometown. His mother was from Kentucky but had come to Colorado after finishing college in Ohio. Her French father had served in Kentucky state government. Kester’s father, whose family worked in the roofing industry, had studied at Denver University and played on the football team.

When Kester was eight months old, his parents left Utah and continued on to California, first settling in Newport Beach where they had friends from Colorado. His father made some land investments and later started working as a supervisor for Southern California Edison. The family settled in Long Beach, where they remained for most of Kester’s childhood. He was an only child with no inherited ties to the arts.

Kester’s interest in art began in kindergarten, largely stimulated by an encouraging teacher. He recalls very decisively, “She was swell. She even had a model come in. It taught us that people didn’t always have a vision in their minds, but that [sometimes] you needed something in front of you. I think it was a valid way to learn. I think the teacher was probably an artist herself…”

Perhaps this role model inspired Kester to take the pathway of becoming an art educator, himself. She made the students aware of art and artists, though Kester was already intrigued. His parents were not artistically inclined themselves, but they were supportive of his talent and interests. They had friends who were art lovers with some art in their home that intrigued him as a small child. “It really didn’t amount to anything, but I didn’t know the difference.”

Having grown up in Southern California and wanting to stay, Kester entered UCLA as an undergrad in the fall of 1945 and he graduated when he was twenty. He declared art as his major from the very beginning because he liked to draw. “At UCLA, I started with painting and drawing and they had a broad spectrum of tools to work with in the art program.”

He quickly realized that he connected more with design and ceramics than with painting. “I also took graphic design. There was no architecture there that early on but there was design, and notable architects taught in the department. They called them ‘shelter’ courses. USC had a good architecture school at that time but I was less interested in engineering, so that was out. I thought of design as a career.” He was a student at the same time as Marilyn and John Neuhart, whom he remembered fondly, and it was an exciting time to participate in the UCLA community.

“The department was small in those days. There were more women on the painting faculty then since there have ever been. One who stood out was Annita Delano.” The art department studios were on the third floor, at that time on south campus, and just down the hall from the music and home economics departments. These years were a growth phase for UCLA and the art department was not yet deeply established, which had its pluses and minuses.

Kester gravitated towards costume design through classes taught by Louise Pinkney Sooy. Sooy encouraged Kester’s design work and she created many opportunities for her students to make contacts in the apparel industry. “She would receive hiring requests and at one point she asked if I would take work designing for a corset company. I’d designed many plates in her class. She liked my drawings… We never learned to sew, just to draw the textiles. She would offer materials you would not normally think to work with. For one project, I designed a skirt that had little holes all over it with tufts of monkey fur sticking out of the holes.”

He liked art and design with an edge and he saw the experimental potential of textiles early on. He appreciated Sooy’s openness and generosity with her students. She would often invite them to her home for seminars. He was falling into a new circle of artists and designers.

Madeleine Sunkees was another textile design instructor who had an impact on Kester with her flawless taste. “She dressed for every occasion. She had her shoes custom made, and she wore very businesslike suits. She was the first lady that I remember with hose that were dyed to match her skirt. Olive green hose, she was blonde, and an olive green suit. She was always the example of what you were there to learn about. Marjorie Harriman Baker was another faculty member who was always dressed for the occasion. Her husband owned Baker Shoes and she always had outfits that highlighted her shoes and hosiery. I noticed because it wasn’t typical of that time.”

Ever the dapper dresser, Kester’s interest in costume and textile design was peaked by these stylish women, and little would ever slip past his acute sense of fashion. A few years later, in 1962, their influence would assist him in his own freelance fabric design work for Robertson Boulevard design firm Crawford & Stoughton.

“I liked costume design just as much as I liked graphic design.” Kester valued and recognized the importance of versatility in a designer. The focus of the UCLA program at the time was on design cohesion. Students learned to design all aspects of a product, from the ads to the packaging. Taking a pragmatic approach, he then “went into ceramics because you made things that you could use. I don’t think I was thinking that deeply about it. I never potted before UCLA. To start with, it was to get a flavor of everything. Undeniably, his connection with renowned ceramist Laura Andreson pushed him further in that direction. She took a liking to Kester, and he deeply respected her. “She was a very dear person. Her own background was in painting. We became close. She was encouraging.”

THE PROFESSOR

Kester continued on at UCLA as a graduate student in 1950. He earned a Masters degree in ceramics, before the university offered an MFA degree. “I prepared to go into education and later got hired to teach ceramics there, but before I was hired back at UCLA in 1956, I taught at Los Angeles City College (LACC), which was on Vermont. That was around 1954.” At that time, the California State University shared a campus with LACC. Kester found himself teaching Cal State freshmen in addition to LACC students. He was getting his feet wet as a college professor.

In 1956, he started working for the art department at UCLA. Jan Stussy was on the faculty at the time. Kester lived near campus and before long he bought a house nearby. He was hired to teach ceramics, but serendipitously, when the weaving teacher left, he took on the courses, which then led to others in the medium. Kester recognized the importance of broad exposure and experimentation in the college experience. He was interested in the organizational and structural side of the department, which made him very valuable to the university.

Starting out in academia, Kester remembered, “You had to work your tail off to get record, doing shows, etc. Laura and I had a joint show at big gallery on La Cienega that was my first when I was a lecturer. It was a stepping stone that helped.” In the summer of 1958, Eudorah Moore, now renowned for guiding the California Design shows, initiated a show of Kester’s work in a gallery space that she oversaw at the Pasadena Museum of Art. “Textiles and Ceramics by Bernard Kester,” included pieces by the artist in his two focal mediums. The two had met sometime around 1954. Traveling in the same small contemporary craft circle, a friendship was inevitable. From the beginning, he “thought she was splendid.”

“The first show I did for Eudie was in the foyer of the Pasadena Art Museum. I gathered up some work. There were modernist and traditional galleries, in terms of the architecture. Several years later she gave me my first one-man show with textiles and ceramics, hanging in the Wentworth Room. She had enduring charm, high standards and “she made sense”.

Kester was becoming a force among craft movers and shakers during the exceptionally fertile years of the California studio craft movement. Aside from his own projects as an artist and craftsman-designer, he established his reputation as an authority through his professorial and curatorial work. He became active in the American Craft Council and its museum. Paul Smith, head of the Museum of Contemporary Craft, would hold meetings and Kester would go out to New York every so often to attend. At some point, Smith asked Kester to organize an exhibition of work from the outstanding university craft departments across the country. Kester traveled to visit the schools and view student projects. The assignment expanded Kester’s relationship with the council, other art departments, numerous emerging artists and it grounded his identity as a curator.

The exhibition they generated, “Emergence: Student Craftsmen” opened in 1963 at the Museum of Contemporary Craft in New York. The show helped increase interest in the professionalization of craft education across the country. Six American schools were selected for inclusion: Rochester Institute of Technology, Cleveland Institute of Art, Cranbrook Academy of Art, California College of Arts and Crafts, the Department of Art at UCLA, and the School of Art at the University of Washington. Work from Kester’s thriving weaving studio at UCLA was included in the show.

Kester was playing an active part in removing the barriers between craft and art, and fine art versus functional art. As an instructor, Kester helped artists evolve and he nurtured a new, evolved body of work. Under his guidance, more expressive forms were able to flourish. Individual teachers like Kester were critical to the legitimization of craft alongside art and design during the 1960s and 1970s. Kester worked closely in the department with Andreson throughout these years and they developed a strong bond. In Kester’s forward-thinking and optimistic view of the era, already “the barriers between art and craft had disappeared.”

As an academician, he contributed to the process for establishing standards in art education. He embraced the idea that an artist should have a total education, grounded in a liberal arts curriculum. The notion of forming a complete person who was versed in a broad base of subjects was his goal as an educator. In order for artists working in craft mediums to receive their due credit, they needed to attain the academic credibility of their fine art counterparts.

Kester was passionate about teaching and energized by the work of his students. Among his most prominent students, textile artist and professor Gerhardt Knodel started his career studying ceramics at Los Angeles City College with Kester. When Kester was hired at UCLA, Knodel followed him there for his undergraduate studies. Knodel credits Kester and Andreson for teaching him about contours and nuance, along with many other fundamentals. It was through Kester’s textiles courses that Knodel became intrigued by the expressive potential of fiber. He appreciated Kester’s Bauhaus-like approach and he explored the medium under Kester’s guidance. Kester later encouraged him to take a job at Cranbrook that eventually led to the directorship in 1995.*

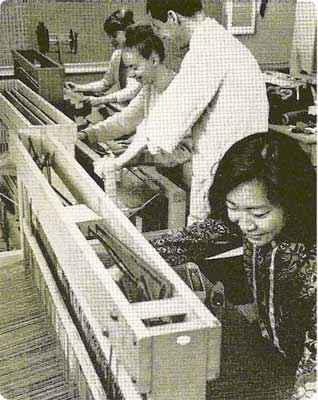

His dedication did not go unnoticed by his students. Ceramist Veralee Bassler and weaver James Bassler, met at UCLA and studied with Kester. When interviewed for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, James Bassler remembered Kester’s nascent weaving studio; “Kester had always been interested in textiles and he started offering textiles, which they wouldn’t even allow in the building, because it takes up space…you can’t have a room with looms and teach anything else. So he found space in Royce Hall, in the basement, next to the women’s bathroom. And that’s where he offered textiles.”

Despite the location, Kester nurtured the vibrant textiles program before fiber art was well entrenched in the art world. Bassler was a student at the same time as fiber artist Neda Al-Hilali. Al-Hilali was living in Houston but she commuted to Los Angeles specifically to study with Kester. At the time, the community of working fiber artists was sparse but on the verge of gaining momentum, largely due to Kester’s role. Kester taught summer courses at Penland, which connected him in new ways with artists from other regions.

Bassler entered the program and decided, “I’m going to go weave China silk…which has probably 300, 400 ends per inch. And I didn’t know anything about weaving but I went over to Kester, who was a kind of personality you never forget if you’ve ever met him. I mean, he’s just very, very kind of stern, with a very critical eye. If he likes you, things are great, and if he doesn’t think you have potential or think that you’re interested in what you’re doing, he won’t give you the time of day. I went over to announce that I wanted to take this class to learn how to weave and I was going to weave China silk. I refused to do a rya rug [unlike] most of his students- they were very popular at the time from the Finnish design influence. Everybody took a second semester of it and wove a rya rug. And I said, ‘I refuse to do anything like that. I won’t do it.’ And he was sort of anxious to have students, you know, particularly a male, because most everybody who could ever find his class was female. And so that’s where I began. And then I saw the folly in trying to weave China silk.”

Bassler spoke about Kester’s critiques that allowed him to move away from purely functional design into a new realm: “Kester was almost encouraging Neda and me to do that, but I had no idea what he was talking about…I think he was more open to the possibilities.” Kester saw the potential in the relatively untapped medium and he opened doorways for his students to explore those artistic possibilities.

Yet, aesthetics and materiality were always fundamental for Kester. He critiqued from a formal standpoint. As Bassler remembered, “He was never interested in why you did it. In fact, he didn’t want to hear it…you got the roll of the eyes. He wanted beautiful.” Each work needed to stand its ground visually, first and foremost. His bottom line was always clear-cut. He wanted work to be striking and he was absolutely decisive with his evaluations. If he disliked a piece, he moved on and there was little or no room for discussion. Kester’s rigorous criticism prepared numerous artists for what they would face as they left the protection of the university environment and became professionals.

By the early 1970s, according to Bassler, Kester was largely interested in teaching graduate students who were pushing the boundaries with their innovative work. Always the designer, he taught students the importance of properly creating installations. “The very first fiber exhibitions were designed with Kester, and they always had such finesse and such sophistication, and we learned a great deal. Even when we had our graduate shows, Kester was there to guide us, giving us the strength to, you know, use sort of operatic kind of colors for the walls, depending on what piece was going against that. So there was real coordination. It was never the white New York kind of wall gallery; it was always color. And he always did that. And he taught us very well.”

Kester found teaching to be very rewarding and challenging work. He enjoyed the rapport of instructing students each semester. In addition to studio work, he taught seminars and courses on the history of textiles, with art history sprinkled in. Eventually acting as Dean of the School of the Arts, he served the university for thirty-seven years before retiring in 1991.

THE WRITER

While rising up in the ranks of academia at UCLA and helping students excel in the art world, Kester was spotlighting the California contemporary craft movement during the pivotal decades as a correspondent for Craft Horizons, the nation’s leading craft publication. His ties to the publication deepened when he, as a young professional, attended the infamous Asilomar craft conference in 1957. He looked back on the monumental gathering as nothing less than “fabulous.”

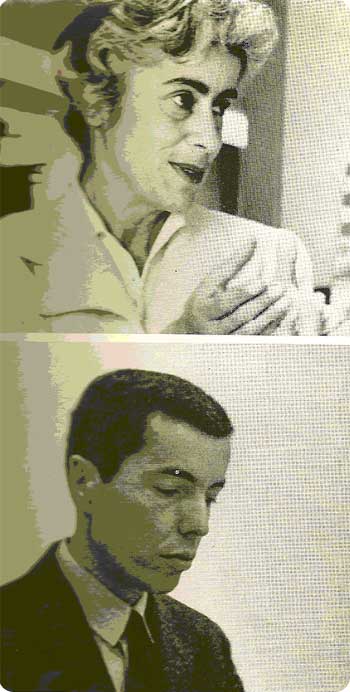

“The great and non-great were there together, hearing it all together, everything that was taking place everywhere, those who wanted to learn, with those who could give.” His only complaint was that it should have happened earlier, and that it could have been longer. By that time, he had already met organizer and craft philanthropist Aileen Osborn Webb, who was in his words, definitively “Swell.” Their relationship would grow over the years.

Kester became professionally and personally involved with pioneering craft activist Webb through his involvement with the American Craft Council that she had created. As early as 1955, he had become the California representative to the Southwest Regional Assembly of the council. Then, in 1963, he was elected Craftsman-Trustee for the Southwest ACC region to succeed Vivika Heino.

When he would travel to New York for meetings and other council business he would occasionally stay in Webb’s expansive townhouse on the upper Eastside. The home had a private elevator and private doorman. He admired her passion for craft, particularly as a woman from the upper echelon of American social elites who, with a more conventional outlook, might have limited her interest to the commonly regarded master painters and sculptors. “We’d eat under a Monet but she had crafts all around, Lenore Tawney at the doorway, and so on.”

On one visit, he had a particularly unforgettable experience in Webb’s home. “One morning she came to door of my bedroom and said ‘Bernard, could you prepare breakfast for the two of us?’ I said yes…He was surprised by the early morning encounter. It turned out, much to his utter and complete shock, her housekeeper was lying dead on the kitchen floor. Kester was stunned into motion. “Pauline was literally dead on the kitchen FLOOR! I got up and got dressed. It wasn’t long before they removed her. The kitchen was copious… so, I made breakfast.”

Kester started writing reviews and other pieces for Craft Horizons in 1963, around the time of the Council’s show, “Emergence: Student Craftsmen”. He selected the subjects for some of his contributions and editor Rose Slivka assigned others to him. She made no promises as to how much space there would be and she would edit his pieces herself.

In June of 1964, the First World Congress of Craftsmen was organized in NYC and he traveled to the groundbreaking event with his colleague Andreson. Kester was serving as an ACC trustee along with Jack Lenor Larsen, Dorothy Liebes and Harvey K. Littleton and several others craft luminaries at that time.

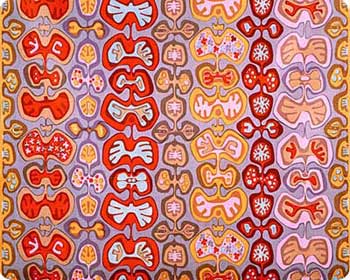

For the 25th anniversary issue of Craft Horizons in June 1966, Kester was asked to moderate a conversation with other textile artist-craftsmen-designers for a feature entitled, “The New American Craftsman: First Generation.” Selected as a representative of “living history,” Kester was described by the magazine as a Los Angeles weaver and fabric printer and teacher at UCLA. Counterpart sessions in other media were led by Peter Voulkos and Paul Soldner on West Coast ceramics, on wood: Sam Maloof, Donald McKinley and Wharton Esherick, among other distinguished figures in the craft scene. Kester led a talk between textile luminaries Ed Rossbach, Trude Guermonprez, and Katherine Westphal.

Kester launched the discussion by mentioning his interest in the changes that had taken place in textiles over the previous twenty-five and even ten years. “We see freedom of the craftsman…to experiment…One of the major factors underlying these (changes) is the scope and scale of materials…the abundance and variety- both natural and man-made. There is a growth in the quality of textiles from industry due, perhaps, to greater competition in industry at all levels of textile fabrication…Very importantly, we find the influence of change in allied art forms affecting the rate and direction of change among textile craftsmen. I think the re-investigation of textile structures of the past has been a stimulating factor- especially since textile craftsmen are now trying non-loom constructions.”

He reflected on the state of fiber arts education and wrote:

“I’d like to think and hope that we are teaching attitudes in design- not only the crafting and designing of textiles, but a way of working with materials, a pursuit that grows by involvement in process, experimentation, discovery and perhaps even conclusion…Teaching of attitudes is part of the training of the comprehensive designer…”

Kester, then associate professor of art at UCLA, started as a regular Craft Horizons correspondent for the LA area in the March/April 1967 issue with coverage of the California Arts Commission’s traveling “ California Craftsmen”. In his writing, he brought attention to the work of numerous artists and venues. He put Southern Californian artists from all mediums in the limelight and made their work enticing to the national audience. Even without the benefit of a visual reference, he made their work significant on the page. The breadth of Kester’s reportage was impressive. He managed to cover much ground and visit a wide span of shows in addition to his academic work.

Putting California’s perspective in the spotlight, he provided informative, adept, unbiased overviews. His reviews hinted at his preferences but emphasized description rather than opinion. In each piece, he would offer detailed morsels of each show, just enough to capture the reader’s interest and reinforce the vitality of the craft scene in Los Angeles as a major art city. He captured the vitality of the scene in Los Angeles, across all mediums. His “Letters from Los Angeles” kept the national audience apprised and elevated the city’s profile. The length of his columns indicated the importance and weight given to the shows taking place out West.

He continued writing for the magazine for several years after Slivka left but stopped once he felt that his articles were being compromised in the late 1970s. High standards are of essence to Kester in each of his pursuits and he refused to compromise them.

THE CURATOR

During the period when he was teaching at LACC in the mid 1950s, Kester became involved with LACMA in its original incarnation downtown, when it was part of the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art. When he started teaching weaving, he inevitably intermingled with the costume and textiles department, as the scholarly textile circuit in Los Angeles was fairly tight. As a result, he was appointed interim chair of the department when the curator departed and he had the opportunity to curate his first exhibition for the museum, which he enjoyed very much. It was a show of elaborate European examples from the permanent holdings called “Woven Embellishments.” Kester reiterated a passion for the non-European textiles in the collection. Curating was a natural channel for Kester’s expertise and interest and it would be a greater focus for him later in his career.

A decade later, Kester helped establish a textile program at Cal State Fullerton. While involved there, he curated a 1966 group show of hand woven, knitted and other work called “The Intersection of Line.” The show foreshadowed his ground breaking fiber show “Deliberate Entanglements,” which was held in 1971 at UCLA’s art gallery, the Wight Gallery. The exhibition proved to be a turning point in the history of contemporary fiber art.

“I proposed the show when fiber first became part of the art scene. Eudie came into the picture when we proposed a citywide program and weeklong symposium to pair with it called, ‘Fiber as Medium.’”

Kester became close with numerous artists through the momentous show, and he traveled with it to install it at other venues, connecting with colleagues throughout the experience. The Wight Gallery sent him to Europe to visit the artists, which was particularly invigorating. Numerous fiber artists came from across the country and beyond to view the show and attend the symposium. It provided a much-needed chance for them to connect and coalesce. After it was over, the UCLA extension program then hired several of the artists to be short-term guest professors. The show was an instrumental vehicle for expanding their reputations and the body of fiber art.

For artists like Kay Sekimachi, the show and symposium were pivotal events in her career: “This brought the Europeans to California and they were doing enormous three-dimensional pieces, some very heavy. It brought Magdalena Abakanowicz and Jagoda Buic to California, also Olga de Amaral and Sheila Hicks was on the program, and Claire Zeisler, too. I do believe that maybe that started the term “fiber art.” They got a number of schools and museums in and around the Los Angeles area to participate in it. There was a wonderful exhibition of Peruvian textiles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that brought Junius Bird out from New York. There was a terrific show of Japanese baskets at San Fernando State College. Anyway, it was very lively and stimulating. People came from all over for the symposium and for the exhibitions. I must say it was all very exciting. In fact, maybe that was the first exhibition I went to outside of this immediate area. Actually, I went with Trude and that was the last big adventure we had together, because we flew down together and stayed in the dormitory and attended most of the events.”

In creating the show, Kester helped push fiber further off the loom and spotlight its potential as three-dimensional sculptural art. He was the portal for bringing these new concepts forward. The same year, “California Design 11” featured several off-loom pieces, undoubtedly due to Kester’s influential perspective and position as Director of the Installation, member of the California Design Board of Directors and jurist for Limited Production and One of a Kind Crafts. He continued in this role for “California Design ’76.” As jurist, he reviewed thousands of submissions in person over a handful of days in Los Angeles and San Francisco. The panel had the task of whittling the submissions down to a couple of hundred selections for each show.

“Deliberate Entanglements” led to other curatorial opportunities for Kester. The first was probably when “the head of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, which was small at the time, saw the show and asked me to do a multi-media craft show. Then he moved to a larger building and we designed another larger show, “American Crafts ’76: An Aesthetic View.” Kester curated and wrote a catalog for the show. After that, he worked on a cross-media craft survey, which was followed by an invitation to curate a textiles show in Kyoto that examined contemporary trends in fiber. While planning it in the early 1980s, he made several trips to Tokyo and Southern Japan and loved it there.

“Some of the fiber was very baroque during that era. I got to meet some interesting people…Claire Zeisler was a divine nut. She smoked endlessly. She was a fabulous woman with endless money and she traveled the world. Her first husband was Mrs. Harold Florsheim of the shoe company. She came to give a lecture in Levis while she smoked…Wonderful eye. Such an interesting lady, she was a world citizen, interested in fiber from all over, she had baskets and things from every culture and she did her own work. Over the years we became close. She was a swell gal. I went out there a lot. She could hire anyone to do what she needed done. She had a huge studio and she had access to leather from her husband. She made a huge piece for a show I did in red leather, very soft, she had it cut. She rethought what fiber was.”

In 1979, he curated “Transformation: UCLA Alumni in Fiber,” and in 1982 he curated and wrote the catalog for “Basketry Tradition in New Form” for the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. The show went on to the Cooper Hewitt and then the Greenville County Museum of Art, South Carolina. As with his writing and teaching, he aided scores of artists in gaining respect and furthering their careers through the exhibitions he organized.

The Exhibition Designer

Without proper display, an installation of even the most enthralling artwork may as well be lost. Few have as nuanced an understanding of the tools for executing a compelling exhibition as Kester, who can draw from so many wells of knowledge, combined with impeccable taste. Kester came to exhibition design in an inadvertent way as a designer of objects and curator, which gave him the ideal perspective and background for accomplishing this work. Opportunities to design shows came to him almost organically. His sensitivity to color is matched only by his grasp of the subtleties of texture. An innate sense of good design combine with sharp curatorial instinct made him the ideal exhibition designer, a role he served for decades at LACMA, in addition to other organizations.

Kester began designing exhibitions when he formed a strong and prolific partnership with “California Design” pioneer Eudorah Moore, whom he met in the late 1950s before she had taken the helm of the shows. Two of Kester’s stoneware vessels and two fabrics, priced at $10 per yard, were selected for “California Design Eight” in 1962. Starting with “California Design Ten,” in 1968, Kester served on the jury for Furniture and Industrial Design and Craft Submissions and as Director of the Installation. He drew upon his UCLA students to assist him with the guerilla-style installations. He continued as a jurist and installation director while serving on the Board of Directors for “California Design Eleven” and “California Design ‘76.” He enjoyed the jurying process and the dialogue that it entailed for the years of his involvement.

In the catalog for “California Design 11,” Moore wrote: “ His meticulous attention to detail, his intimate knowledge of the materials in the exhibition as well as his talent in eliciting the utmost in effort from those who work with him, make him invaluable.”

Another one of his early forays into exhibition design came from LACMA, where he would later become the official in-house exhibition designer. Kester took on the role from the very beginning when the Wilshire Boulevard location debuted in 1965. With Kester’s advocacy and assistance, the decorative arts department boldly launched its galleries at the opening with a craft show, “Craftsmanship,” much to everyone’s amazement, remembered Kester. He had seen the show in New York at the Museum of Contemporary Craft and facilitated the process since the curator of the department was a historic specialist who had little experience with craft. He revisited this role in the 1990s as he entered retirement from academia, when he was free to focus more energy on his exhibition design work. He continued at LACMA for almost two decades.

Across the street in the late 1960s, Kester became involved as an advisor to Edith Wylie and her Egg and the Eye gallery, eventually designing many shows and serving as a board member for the Craft and Folk Art Museum that she founded on site. “Artists would come to town and exhibit. Edith Wylie provided a forum.” Wyle knew Kester through the UCLA art crowd, since she had studied there. “She wanted to mix craft into her shop and that was one of the best things that happened here. She was so persuasive and a dear person. It was fabulous! The gal who ran the place had great bravery to do it. Edith knew a lot of artists. The atmosphere was not reserved.” Kester enjoyed the way that Wyle created something that was more than a store. It was a living room for the craft world.

In Wyle’s words, “Bernard Kester was invaluable to me in the early days…I met him way, way back at the beginning of The Egg and The Eye… I was trying to design the exhibitions, and one day I happened to visit Eudorah Moore, who was doing her California Design shows. And I was in her office, and I said something about how I needed help, when suddenly a voice said, “You certainly do.” [laughter] Bernard Kester emerged from behind the screen.”

Kester designed and curated many of the contemporary craft shows at CAFAM over the years, including, “California Women in Crafts” with Rita Lawrence of Architectural Pottery and, perhaps most significantly, “Made in LA,” which was a bicentennial look at contemporary craft in 1981. The venue was pulsing with activity and it was exciting to contribute to it.

Despite all of his pursuits, his own original work as a designer and craft artist remained on the back burner throughout. Kester found the pathway that would allow him to serve the art world most effectively. His early artistic endeavors were overshadowed by these accomplishments. He humbly dismisses their significance. “The monkey skirt was a very different time frame.”

In more recent years, Kester feels he has become out of touch with new craft artists. “There have been developments that seemed impossible in the past. I don’t think the art world has lost momentum. But I think it was an exceptional time when I was teaching. Craft was exciting then. Now craft has entered everywhere. UCLA is no longer the center of everything. I don’t know where the center is now. Universities are less sympathetic to art. The things that go on are less emphatic and severe in their newness than they used to be. Yet, people are scared away from craft, regardless of what you call it.”

___________________________

Interview with Bernard Kester- Friday, November 25th, 2011 12:30 pm, Los Angeles

*AAA Interviews:

James Bassler, 2002 Feb. 11-June 6

Gerhardt Knodel, 2004 Aug. 3

Edith Wyle, 1993 Mar. 9-Sept. 7

Craft Horizions articles