loading...

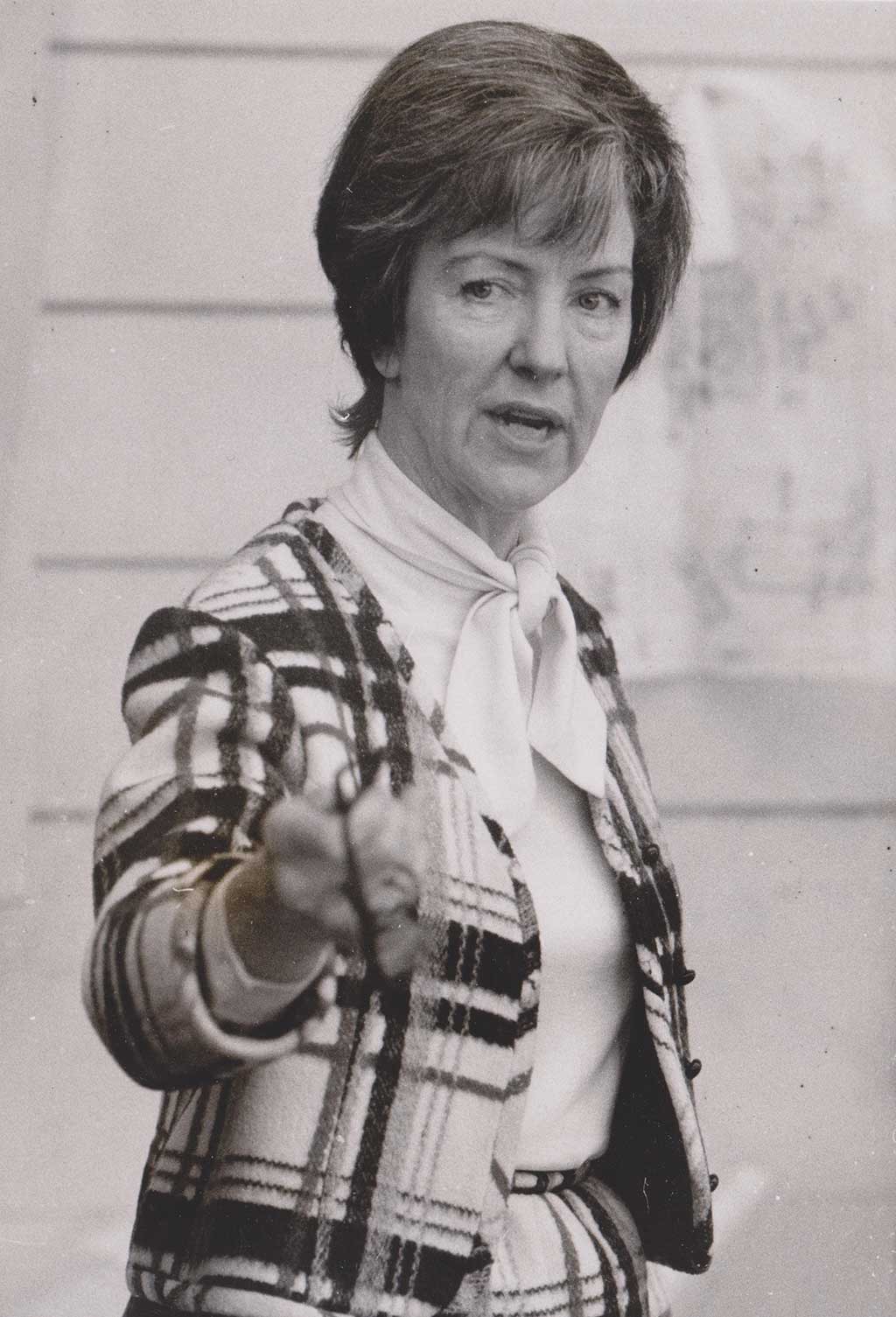

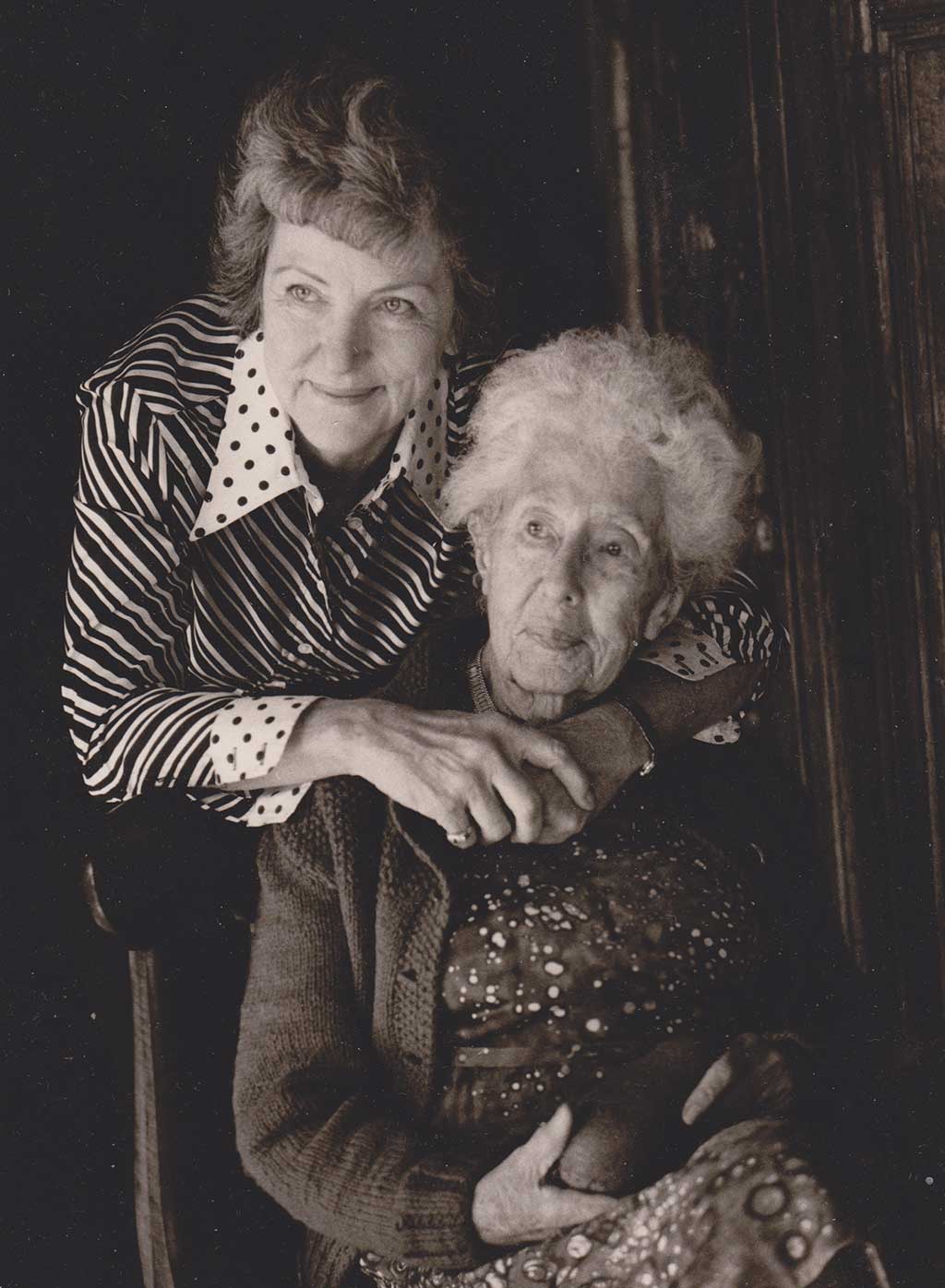

Eudorah M. Moore

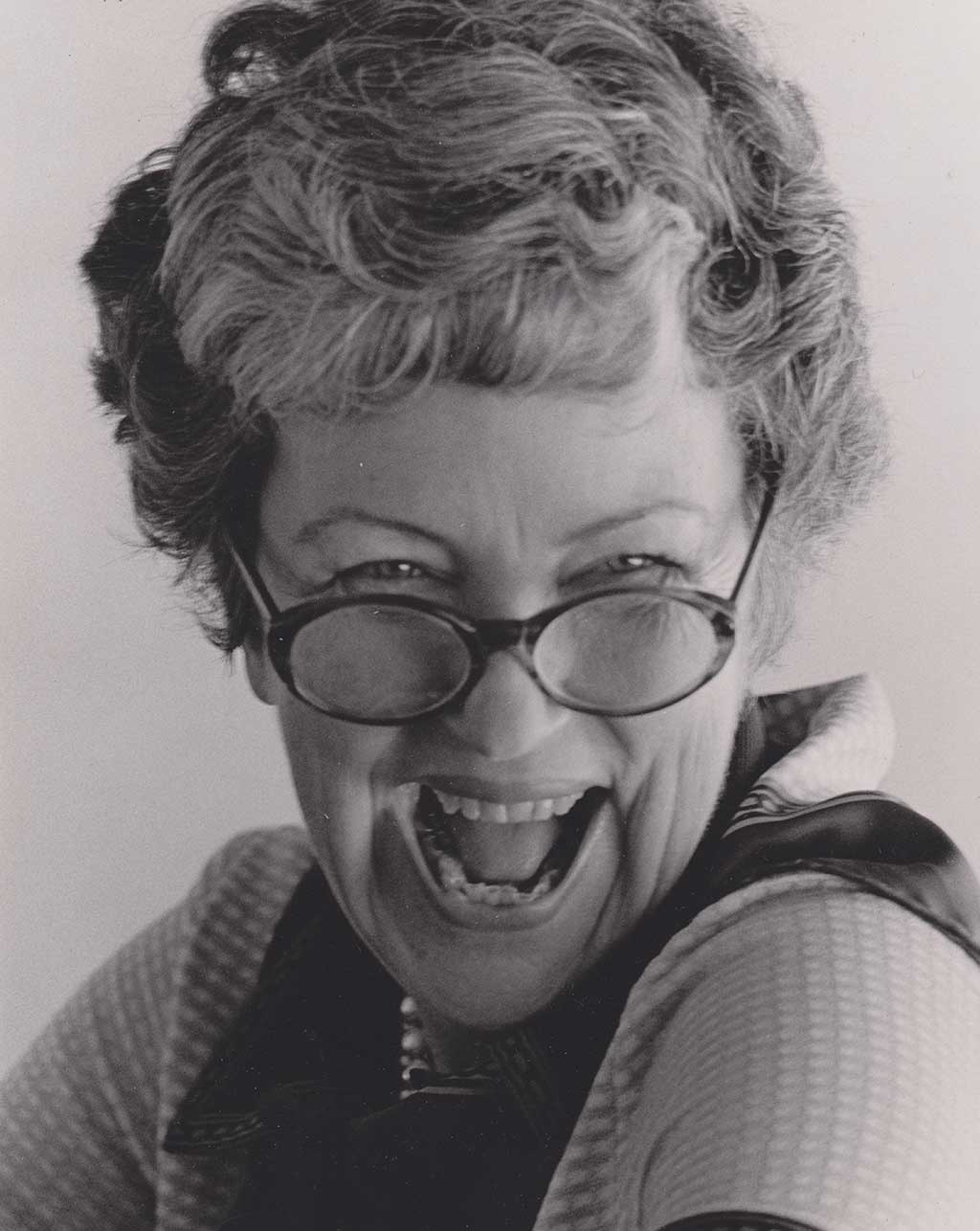

Eudorah M. Moore, who describes herself as a “protagonist for the crafts,” has spent a great deal of her life advancing and promoting the work of the hand. She recalls:

I think the way that I first became aware of the crafts, and therefore interested, was as a child going with my mother up high into the Appalachian highlands where there was an old chair maker who still spoke the Elizabethan English…We used to go up and collect his chairs because my mother loved them. It made me very, very conscious of the quality that went into really deeply traditional crafts, like the fact that the chairs never had a nail in them. The parts would bond together as the wood dried. They ended up being what they called ‘settin’ chairs. You can picture the old boys sitting back in their chairs and just settin’ against the house wall.

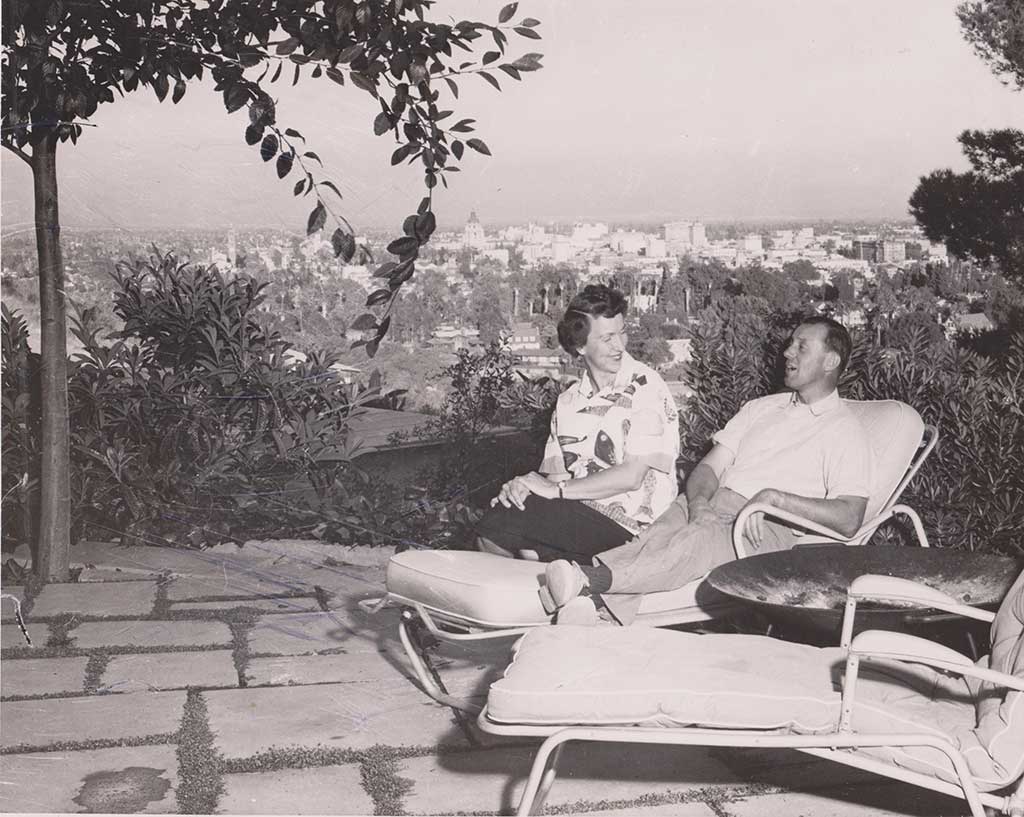

Armed with this innate consciousness and her unflagging optimism, Moore, who graduated from Smith College, married and made her home in Pasadena with her husband and four children, became a driving force in what she likes to call the “New Crafts Movement”: …a recognition of different kinds of contemporary crafts that were often created as artworks by college educated people, and not just as functional objects. That was a whole other level of consciousness when relating to the crafts, and it’s the one that certainly I’ve spent my life in.

California had a leading role in the “New Crafts Movement.” The central artists had gone back to college on the G.I. Bill and were applying a college attitude towards these age-old materials. This made a huge difference in what was produced. People who came back from the war had the opportunity to move into the art department. There was enough of a demand that all the crafts materials were included for the first time in the university curriculum, where pure research was often the mode. It brought a new dimension to the way people looked at the crafts. In Moore’s perception:

…there was an efflorescence that was unbelievable. Art attitudes were assumed rather than the craftsmen’s attitude, which was to make an object of use.

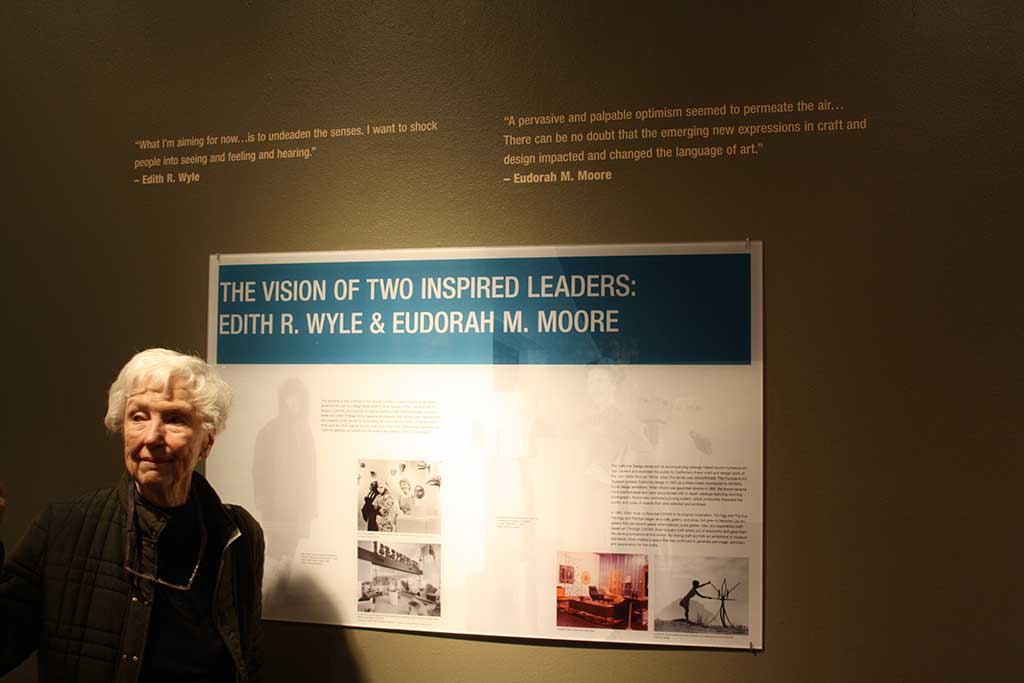

Moore became deeply involved in the life of the Pasadena community. She was a founder and first president of the Pasadena Art Alliance. She served on the boards of many cultural organizations including the Pasadena Arts Council and the Otis Arts Association. She was instrumental in the early planning and development of the new Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum) in the late 1960s, having initiated the activities for its creation and then serving on its Board of Trustees. Perhaps the most important work Moore would do began in 1961 when she, as a board member, asked then director Tom Leavitt if she could reorganize the “California Design” exhibitions that the museum had been putting on.

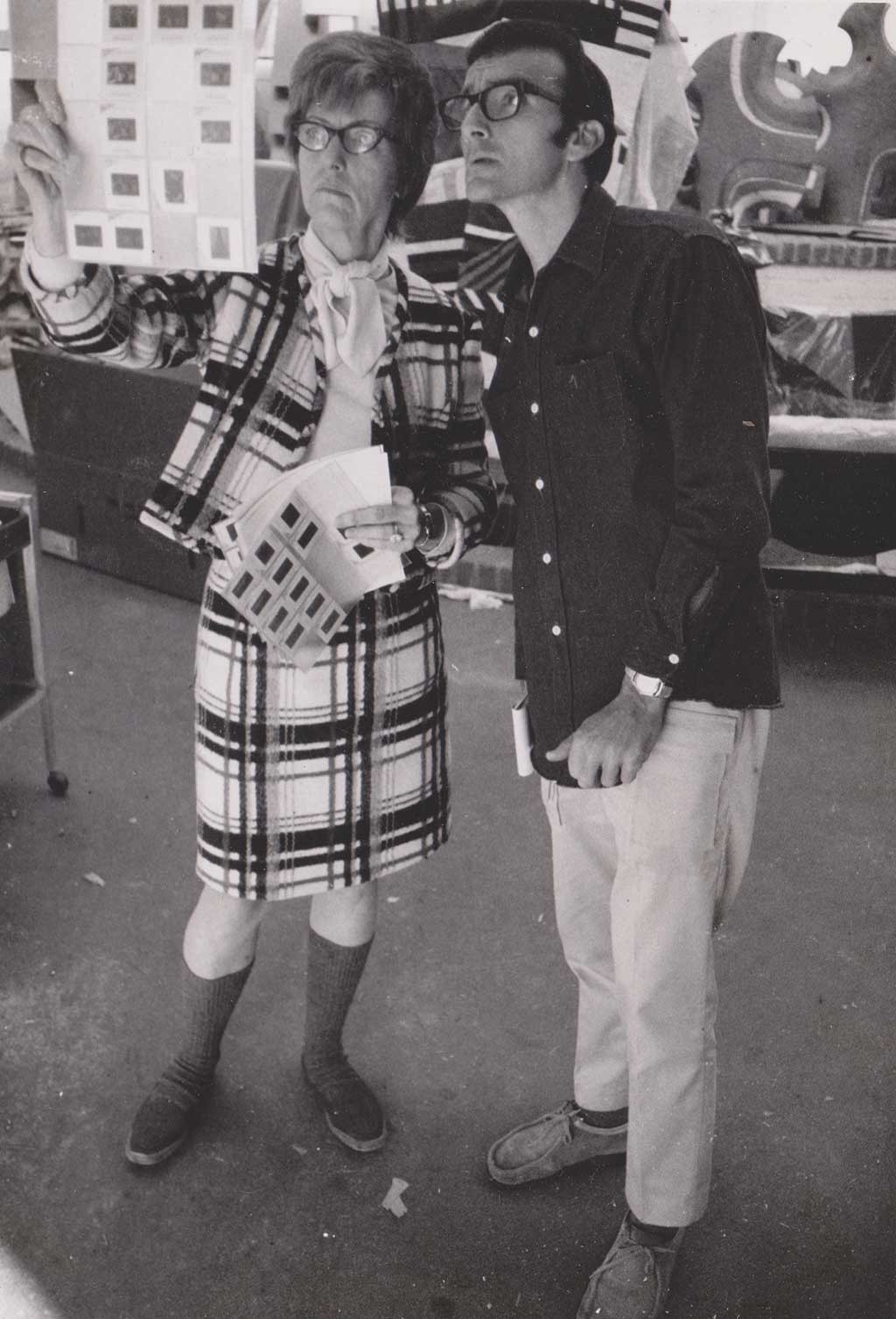

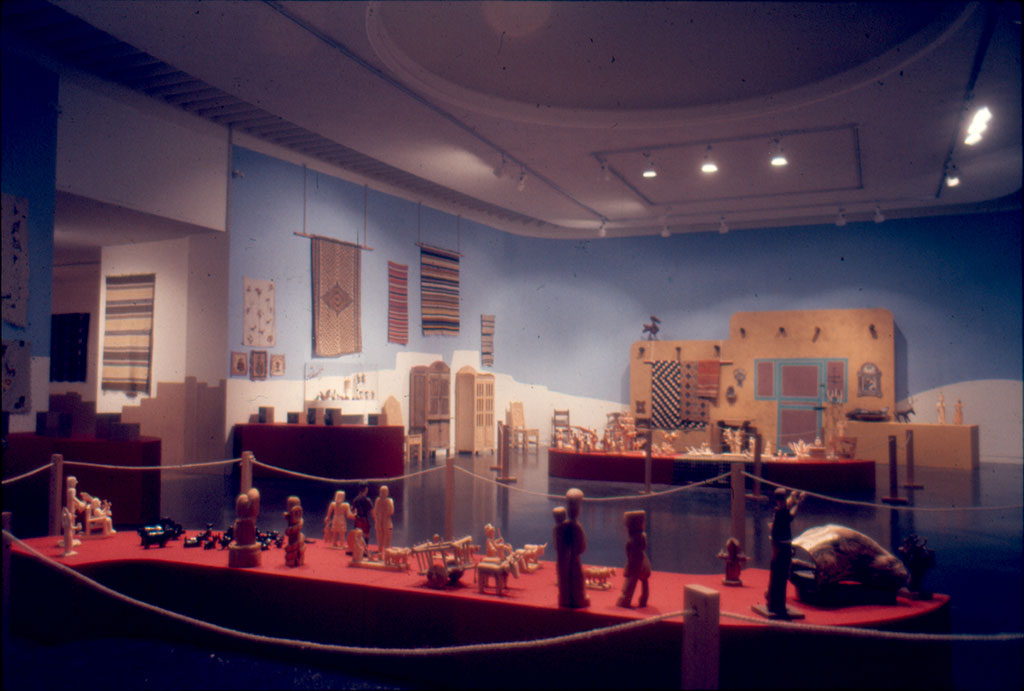

The first seven “California Design” exhibitions had been annual shows of contemporary furniture from the Los Angeles Furniture Mart. Moore, however, had a different vision for the exhibitions; they became triennial, were juried, and potentially included virtually any object of quality made or designed in California from tea cups to small aircrafts to children’s play equipment. Moore became Curator of Design at the museum in 1962 and held that position for 15 years. She was also named Director of “California Design” (which later became a separate nonprofit organization) dedicated to exposition, education and publication in the fields of architecture, design and the crafts.

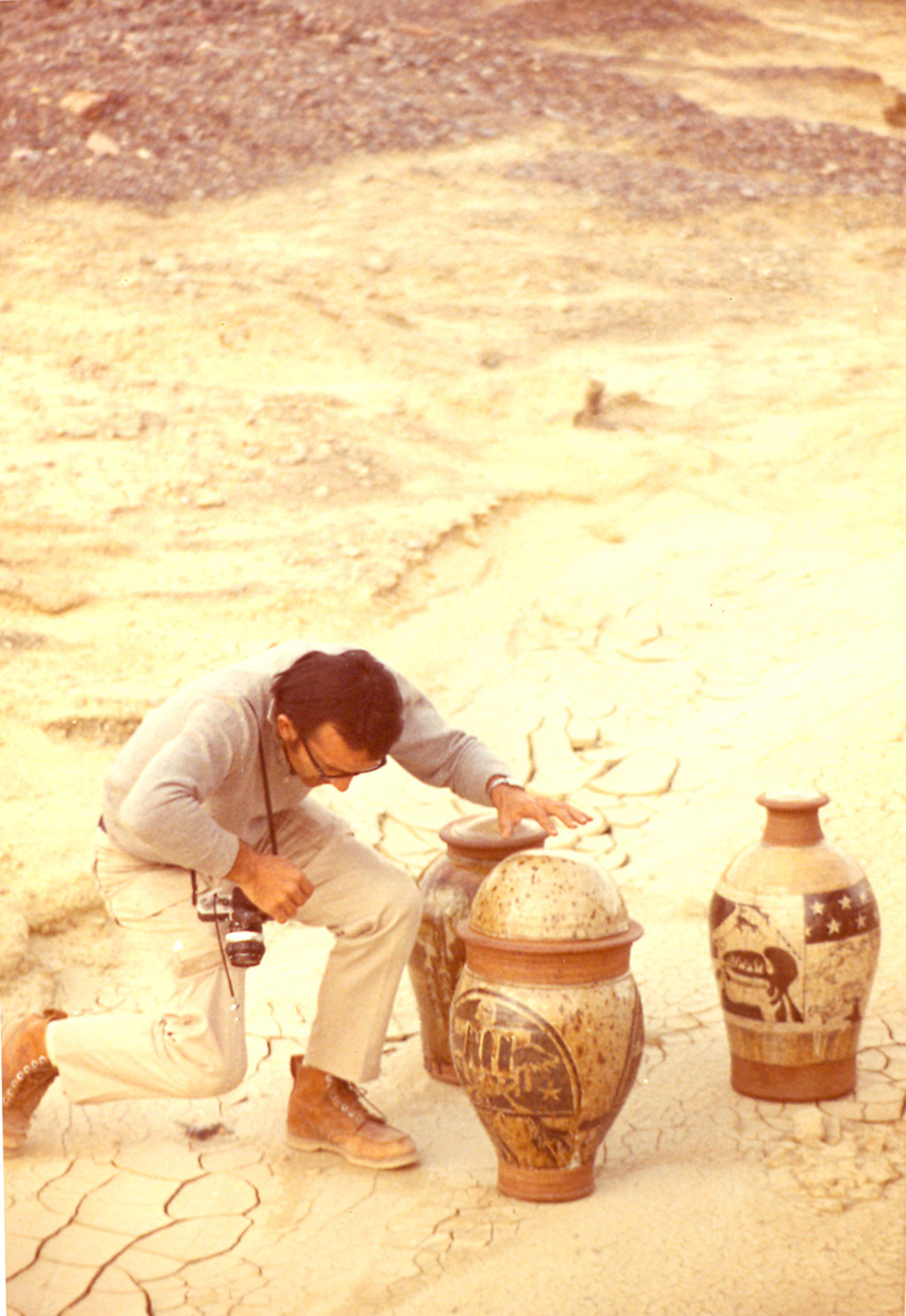

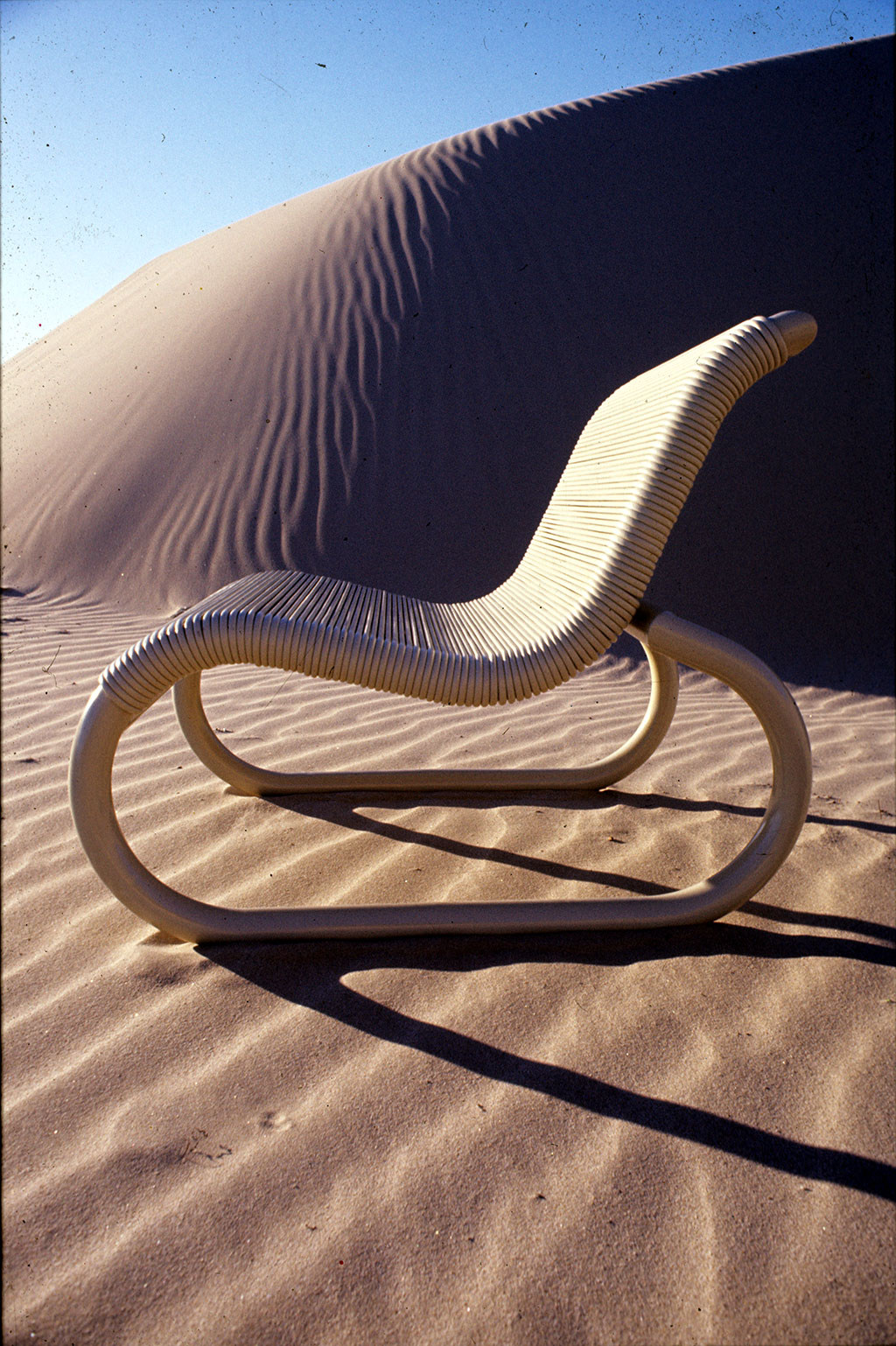

Her visionary work on the exhibitions led to a unique coupling of design and craft. The exhibitions and accompanying catalogs caused reverberations throughout the United States. Combining artist-designed furniture with handthrown pots; wooden rocking chairs with hot tubs; plastics with natural materials and photographing (together with photographer Richard Gross) these diverse and exciting objects in California’s spectacular natural landscapes was a breakthrough moment for craft and design. Moore likes to describe her approach as a bridge between design and industry, which was demonstrated and verified by the “California Design” exhibitions. Her championing of the handmade elevated the work of dozens of artists while illuminating the importance of the crafts. The shows acted as a catalyst between manufacturers, craftspeople, architects and the public. They received international editorial attention.

Moore looks back on her ideas for the “California Design” exhibitions:

It was very unusual, actually, to mix design and craft, and it was particularly pertinent at the time that we did it. I’m not positive that the two fields would be able to establish such dialogue anymore as they did then, but, at the time, as I talked to industrial designers, I felt that the process of design was very much the same as that of the process of crafts. I can remember talking to Charles Eames about this, and his saying ‘they’re exactly the same. The only thing that’s different is the foreseen hand. When I’m designing these chairs, I’m designing them with the idea of coming in multiples. Our idea is to get the cost down. The process is the same, although the final intent is different.’ And it was that dialogue of the processes that kept the shows quite lively, and why we included both.

The “California Design” exhibitions, in Moore’s view, had a special ingredient, the craftsperson:

One of the things that intrigued me in putting up the shows was that all the craftsmen came up out of the woodwork and volunteered at the museum and wanted to help, doing whatever they could, not just for their own piece, but for everybody else’s piece. I can remember installing those shows at the museum and having literally fifty different volunteers who were helping us. There was that real sense of brotherhood.

The manner in which artists were chosen to exhibit in “California Design” was in itself unique. Pieces were not judged by slides; rather, the jurors considered the actual pieces that were submitted in person. Artists brought their works to locations in Northern and Southern California. The pieces were deposited, juried, and rejected pieces were picked up. Moore describes the jurying process:

I felt very, very strongly that the only way to jury an object was to look at that object. It was such work as you can’t imagine. We had a jury of three people for the crafts. We received thousands of objects from which we chose an exhibition of about five hundred. Then the photography started. We would receive in September, jury, and have the catalog ready for the show in March. It was an arduous thing.

Because she understood the historical significance of the “California Design” shows, Moore insisted the exhibitions she directed have catalogs. Those for “California Design VIII, IX, X, XI, and ’76” are historical records of the fertile imagination and skill of the artists who were represented in the exhibitions. In addition, the creative and forwardthinking photography used in the catalogs married craft and design with exteriors to accentuate the beauty and originality of the objects. The force behind this ingenious formula was Moore. In addition to the “California Design” series, while at the Pasadena Art Museum, Moore prepared and edited books and filmstrips on design as well as organizing and mounting a variety of other exhibitions and activities in the crafts, including: “Islands in the Land,” about traditional crafts; the international fiber symposium, “Fiber as Medium”; and the historical exhibition about the Arts and Crafts movement before it was on anyone’s radar, “California Design 1910.” As she saw artists coming in with their objects at the last design show in 1976, she realized that she wanted to publish something that told about the craftspeople themselves and their way of life. This was the genesis of a book titled The Craftsman Lifestyle: The Gentle Revolution.

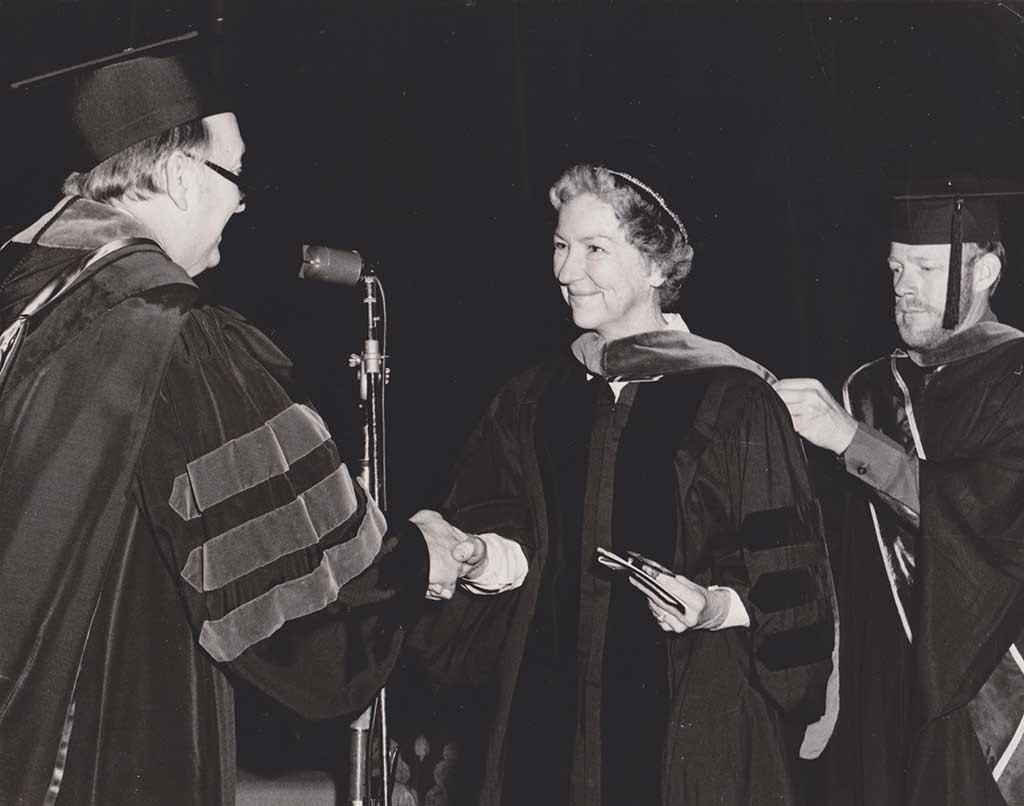

From 1978 to 1981, Moore went on to serve as Crafts Coordinator of the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C., with responsibilities for all craft-related endowment grants and activities. Under her leadership, a number of grant categories were added including Building Arts and Crafts Projects. She also developed an advocacy program aimed at generating commissions and bringing public attention to the crafts of architectural scale and crafts integral to architecture. She supported a number of activities aimed at increasing scholarship and developing better communication in the craft field. Moore initiated and directed a broad participatory effort to identify the needs of the field. The findings of this effort, known as the National Crafts Planning Project, were brought to a National Crafts Congress.

One might wonder how the art versus craft controversy, which was front and center throughout her career, affected Moore’s approach to the crafts. In a 2001 interview for Craft in America, her opinion was strong:

I don’t think that there is any question but that there is an ongoing art/craft controversy. My point of view about this is the fact that the entire creative act is one. My feeling is that the term ‘art’ actually is an accolade. It doesn’t have anything to do with intent, really. This person is an artist. And, to me, that person can be a craftsperson, maybe a potter, for instance. But some of the people who practice in those different categories are artists. And then, many people who paint and make paintings are not really artists at all. So, my feeling is that the word ‘artist’ is an accolade that is given by others. And the word ‘craftsman’ is a noble word from my point of view because it bears back to tradition and to the formation of all objects of use with which we surrounded ourselves.

I understand that some people think that the word ‘craft’ is a pejorative word that has negative implications and I disagree with that point of view entirely because I think it binds this activity to the human race. It allows possibility to well up from below. It allows humanity to come in rather than elitism.

Her views on creativity and art are compelling:

I think all art is energy transfer to some extent; and the crafts, because of their hands-on nature, are very much so. In some way, you can sense when you look at a piece that has that energy, you can feel it; it is transferred. But that’s through time. You look at crafts through time and you can sense the energy of the makers. And I think this is one of the moving qualities of it; the palpable qualities of craft. And also the fact that the crafts essentially transcend time and they transcend styles. When you touch a pot that bears the imprint of the hand, it has that strength of the maker.

Moore’s commitment to the arts continues as she is often invited to participate in conversations about the “California Design” exhibitions, the climate for the crafts in America now and the future of the handmade. When asked by curators Jo Lauria and Suzanne Baizerman to write an introduction to their book, California Design: The Legacy of West Coast Craft and Style, Moore wrote:

Now, thirty years after the last “California Design” exhibition in 1976, it is interesting to note that the best work of this period is re-emerging, being re-evaluated and being found as sound and interesting as ever. Time has silenced some of the strong voices, others are still productive and fresh, but review of the work reinforces the belief that quality speaks across generations and has enduring value.

In this statement, Moore could be speaking about herself. Certainly her work, which stands as a documentation of the golden age of craft in California and the nation, is as sound and as interesting as it was almost fifty years ago. The quality of her work speaks across generations and has enduring value.